(If you need to order custom term paper on the topic of linited resources, you have to leave a request via form at the main page.)

The media is full of peak oil refutations. Unfortunately for the pundits, while they’re heavy on rhetoric they tend to be short on data.

In comparison, way back in 2009, Praveen Ghunta, used the BP Statistical Review of World Energy to make a list of countries past peak oil on his True Cost blog. He updated the data again in 2011.

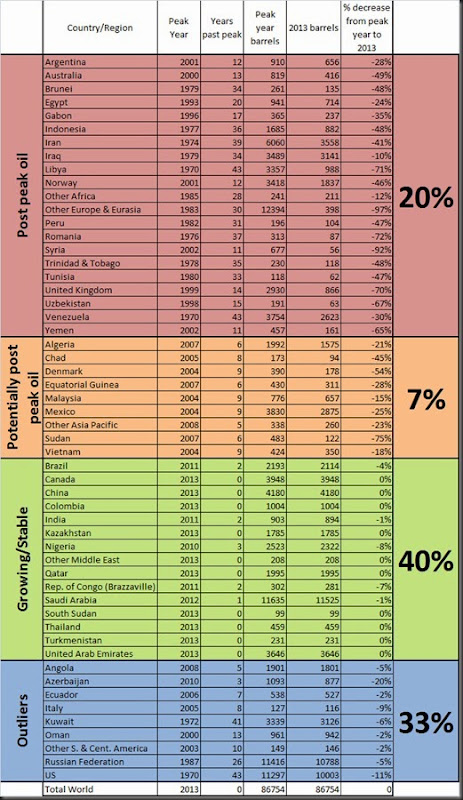

Taking Ghunta’s work as a base I have followed up with figures from the 2014 BP Statistical Review of World Energy. I have purposefully been much more conservative in in defining what a country past peak actually looks like: I have made the arbitrary decision that any country or region that peaked more than 10 years ago and produced a minimum of 10% less oil in 2013 than in the peak year has officially reached peak oil. That is of course is the point in time when the maximum rate of extraction of oil is reached, after which the rate of production is expected to enter terminal decline. Peak oil is only visible through hindsight and so I have taken a cautious approach to assigning exactly which countries and regions are past peak. Peak oilers have long been far too quick to draw conclusions based on questionable data and so I am trying to avoid this same pitfall.

It is worth noting that terminal decline is not always inevitable as we have have seen from the stunning turn around in the United State’s production figures. How long this will actually last and how applicable the United State’s shale oil technology is to the rest of the world is yet to be seen. Too many factors play into oil production to make any strong predictions for the future.

That being said, Luisa Cipollitti an official for Statoil Venezuela recently commented that half of the world’s 163 biggest oil projects require a $120 price for crude oil. Given the current plummeting oil prices many projects could be delayed or cancelled if those prices stay low. This in turn could hurt global production in the coming years. At the time of writing Brent crude prices were sitting around $85 a barrel.

The truth is that peak oil is happening in a number of countries and regions throughout the world. It’s just happening in a way that many of the doomsday peakers never imagined. John Michael Greer appears to be correct in coining the term “the long descent.” We can expect to see periods of growth truncated by recessions which push greater and greater proportions of society to breaking point. We will also see an increasing number of countries and regions hitting peak oil. Some will decline spectacularly such as Australia, Norway and Yemen. Others will carry on for many years on an undulating plateau. Yet others still will see production gains due to new technology making olds fields viable once more. The only thing for certain is that the future will be messy.

It is worth noting that a number of politically unstable countries such as Iraq and Syria and sanctioned countries such as Iran are more than likely not physically past peak. However their difficult political/conflict situations make external investment untenable for many players. It is unlikely they will stabilise enough for production to increase in the near future and so for all intents and purposes they are past peak. Including these countries and those potentially past peak, 27% the worlds production comes from countries and regions that are past peak oil.

A full 40% of countries and regions appear to to stable and/or growing. Most of these countries are relatively politically stable and so are attractive for investment. However, ongoing trouble in Nigeria has seen a pullout of some major players which has led to a lack of development of new fields and the Republic of Congo has seen a number of major fields pass peak.

The most interesting sub-group is that which I have classed as ‘outliers.’ These countries account for 33% of 2013 production but don’t follow any discernible pattern and so need to be looked at individually.

Angola’s production has been stagnant due to persistent technical problems with some projects. Despite some new fields coming online since 2008 rapid depletions in other fields has led to steep decline rates.

Azerbaijan’s production has suffered from unexpected technical problems at its largest fields. New projects such as the Chirag Oil Project, may boost Azerbaijan's production. Then again, it might not.

Ecuador rejoined OPEC in 2007 after leaving in 1992 due to OPEC’s high membership fees and refusal to allow Ecuador to raise production. Since then Ecuador has remained relatively unattractive to investment due to socialist government initiatives to retain a higher share of oil profits.

Italy banned offshore drill in 2010 following Deepwater Horizon and is only now beginning to allow some offshore projects. Italy first produced over 100,000 thousand barrels of crude in 1996 and has bounced along roughly 20,000 barrels either side since then.

Kuwait has struggled to boost oil and natural gas production for more than a decade due to project delays and insufficient foreign investment. A shake out of the state owned oil company was made in 2013 in order to try and address these issues.

Oman has technically difficult plays which are expensive to extract. Oman's fiscal breakeven price for oil in 2013 is $104 per barrel. DME Oman prices ranged between $101.69 and $95.28 per barrel in September 2014.

Most of the smaller Central and South American producers maintain relatively socialist governments with inflexible profit sharing arrangements. These countries therefore struggle to attract overseas investment to develop new wells.

The Russian Federation has a number of new projects in development but these are expected to only offset declining output from large aging fields. New technology is seeing better recovery rates from current fields.

Already mentioned, the United States has seen an unprecedented increase in oil production since 2008 due to a huge increase in exploration and drilling in previously unprofitable shale oil fields. It is highly debatable how long this boom will last. The latest EIA report forecasts a long, slow production decline after 2021 while the Post Carbon Institute put a report out last week predicting a peak before 2020 with production levels just one tenth of what the EIA forecasts by 2040.