One of the many hypotheses put forward by peak oil theorists is that as the production of conventional oil peaks we will see increasing volatility in oil markets. The basic reason for this is that oil is the fundamental energy resource on which our modern industrial society runs. Economies begin to falter under the pressure of high oil prices as they can no longer sustain growth and so demand for oil falls. As demand falls, so does the price of oil which eventually reaches a level that is conducive to economic growth. Demand increases again followed by the price of oil and the cycle repeats ad infinitum. That is of course until you throw a proverbial spanner in the works in the form of restrictions on the supply side. Historically the most influential spanner has been unrest in the Middle East. However we are increasingly seeing the impact of another much larger and altogether much more catastrophic spanner: the peak production of conventional oil.

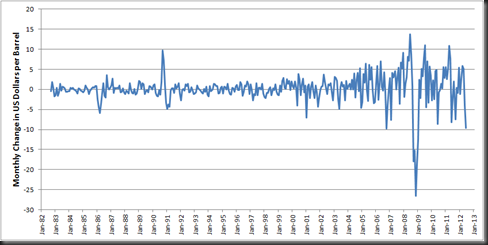

Just look at how much more volatile prices have become over the last 30 years:

Figure 1: Monthly change in price for crude oil (US dollars per barrel), simple average of three spot prices; Dated Brent, West Texas Intermediate, and the Dubai Fateh, August 1982-June 2012. Data from http://www.indexmundi.com/commodities/?commodity=crude-oil

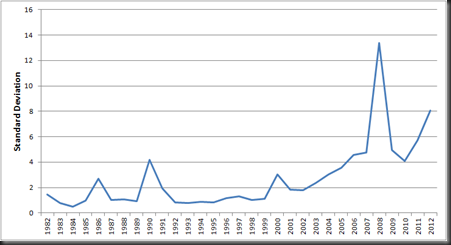

Figure 2: Standard deviation of the monthly price change for crude oil (US dollars per barrel), simple average of three spot prices; Dated Brent, West Texas Intermediate, and the Dubai Fateh, August 1982-June 2012. The standard deviation provides a numerical measure of the overall amount of variation from the mean in a data set.

Figure 1 and 2 clearly show that something has been happening to oil prices since perhaps the early 2000s. Visually large changes before that can be attributed to the oil price bubble bursting in 1985 due in part to a massive increase in rig counts, the 1990 Iraq War and the Dot-com bubble beginning in 2000. Some of this variation post 2000 can be attributed to the American invasion of Afghanistan and Iraq (2001 and 2003 respectively), the global financial crisis of 2008, the Arab Spring beginning in December 2010 and the current Syrian crisis. But this doesn’t explain the whole story either. We are in a new era where oil prices are unprecedentedly being affected by production constraints. Figure 2 shows that since 2005 the data values are more spread out from the mean, exhibiting more variation than any other time over the last thirty years except for the 1990 Iraq War. Coincidentally 2005 is also the year when global conventional oil production tailed off: rising only 0.5 per cent between 2005 and 2011.

Up until this point it has been a somewhat subjective analysis. No hard statistics have been carried out. I wanted to see just how different the volatility in prices post 2000 were compared to the rest of the data set. For those of you not interested in the mathematic side of things you can skip this part and go right to the results. But in the spirit of academic openness I would like to explain my methodology.

Methodology (The Sciencey Stuff)

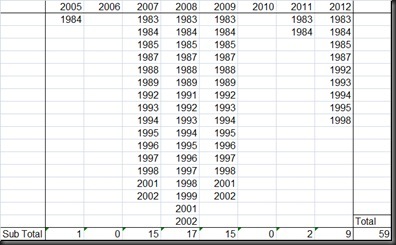

The data used to create Figure 1 was split into annual groups 1983,1984 etc and converted into their absolute value so that all numbers were positive. Because the monthly oil price change between years was being compared it didn’t matter if the change was positive or negative, just that it changed. A one way ANOVA test was used to determine if there were significant differences between groups of data (i.e. each year). Due to carrying out an ANOVA test the ratio of the smallest to largest standard deviation could be no more than two (clearly not true from Figure 2), so the figures were transformed to log10. This also ensured that the data followed a normal distribution. The data point from May 2007 was removed as that figure was 0 (i.e no change in oil price from the month before) and could not be calculated to log10.

Using Daniel’s XL Toolbox plugin for Microsoft Excel the ANOVA test was calculated along with a post-hoc Bonferroni-Holm test. Post-hoc tests are carried out in order to find patterns or relationships between subgroups of a data set and the Bonferroni-Holm test is generally known as the most conservative of all post-hoc tests. In this case the relationship being determined was whether or not the change in oil price within one year was significantly different than any other year.

The null hypothesis is that there is no significant difference in monthly oil price change between years. The alternative hypothesis is that there is a significant difference in monthly oil price change between at least two years.

Results (The Interesting Stuff)

Just a couple of scientific results before we get to what we are really after. The F-value for the above ANOVA is 6.991 and the p-value is 3.02E-21. Because the p-value is less than 0.05 we can reject the null hypothesis and be certain that there is a significant difference in monthly oil price change between at least two years, possibly more. But which years exactly? This is where the Bonferroni-Holm test comes in.

Figure 3: Statistically significant Bonferroni-Holm test results.

Figure 3 shows the how the only statistically significant differences in monthly oil price changes between years occurred after 2005. In other words between August 1982 and December 2004 prices rose and fell relatively benignly compared to what happened after 2005. We can see intuitively in Figure 1 what we are told statistically in Figure 3. The mid to late 80s and 90s saw little volatility in oil prices bar the 1990 Iraq War and stayed relatively calm right up until the 2003 Invasion of Iraq. Oil prices haven’t stopped see-sawing since with the first statistically significant difference seen in 2005.

This is only one data point however and we don’t see any grouping of statistically significant volatility until 2007 when the global economy began getting the jitters with concerns surrounding the US housing bubble. The next two years were havoc on the oil markets as prices bounced up and down trying to find some sort of equilibrium. 2010 and 2011 saw a period of calm as the the economy finally readjusted. All was not well though as oil prices this year have so far been the fourth most volatile in the last thirty years.

Conclusion

With the production of oil from conventional sources almost stalling since 2005, concerns about the collapse of the Euro zone still very real and the unknown outcome of the Syrian civil war we are living once again in very uncertain times. This is reflected in the volatility of oil prices so far in 2012. At the time of writing West Texas Intermediate crude was at US$93.25 and Brent crude was at US$112.00. So far this year WTI has fluctuated between $80 and $110 per barrel and Brent between $90 and $123 per barrel. Price fluctuations like this are a double whammy of bad omens. They are neither a sign of healthy economy nor conducive to growing an economy.

I am not the first person to point this out. Shiu-Sheng Chen and Kai-Wei Hsu from the National Taiwan University published a paper this year in the journal Energy Economics that showed how trade between countries decreases when there is high oil price volatility. Gregor MacDonald over at Chris Martenson’s Peak Prosperity has an article on how oil price volatility kills economic recovery. John Timmer at Arstechnica discusses the implications of the paper by the University of Washington's James Murray and Oxford's David King in Nature, published earlier this year. Murray and King argue that once demand consistently exceeds oil supply the economy enters what they have coined a "phase transition." They believe we'll be in the volatile phase from here on out.

Chris Nelder at Smart Planet wrote in June that spare capacity will “drop to critically low levels in late 2014/early 2015 as depletion finally overwhelms our efforts to fill the gap with unconventional oil, kicking off a long era of harsh volatility in both oil prices and the global economy as a whole.” “So enjoy the relative stability of the next two years, and take advantage of the narrow ledge concept to trade oil profitably as it bounces between the price floor and ceiling.” Looking at the results I’ve calculated above I don’t think we are looking at a period of relative stability for the next two years. This means the economic situation could be even worse if Nelder’s predictions come true in late 2014/early 2015. We are seeing high oil price volatility right now.

John Michael Greer of the Archdruid Report published a paper in 2005 titled How Civilizations Fall: A Theory of Catabolic Collapse. His main thesis is that “as societies expand and start to depend on complex infrastructure to support the daily activities of their inhabitants” it becomes increasingly energy intensive to maintain this infrastructure. Eventually “the maintenance needs of the infrastructure and the rest of the society’s stuff gradually build up until they reach a level that can’t be covered by the resources on hand.” What follows next is catabolic collapse, where the society reverts to a level that can be sufficiently maintained, at least for a while. After a time the society becomes anabolic, or begins to build up again until it reaches some new limit and then collapses again. Greer argues this is what Chinese and other societies have done dozens of times throughout history. He believes our current oil based society is in the clutches of catabolic collapse at the moment (it should be noted that collapse refers to a breakdown over a period of years, not some kind of biblical apocalypse).

Whether or not you subscribe to the idea of peak oil it is undeniable that oil markets have been more volatile over the last five to seven years than at any other period. We have entered a new paradigm where oil prices are marked by extreme fluctuations. This volatility is damaging to economic recovery in a time when many countries are already limping along propped up on huge amounts of foreign debt and little to no economic leadership. Oil price volatility is the new norm and there is nothing anyone can do about it bar an unlikely societal shift to a low energy society. The best response is at the personal and local level by reducing your reliance on fossil fuels right now in every aspect of your life. At the very least when things deteriorate over the next few years you will have an extra layer of resilience.

It may be more meaningful to convert the monthly USD changes in price into 1982 US dollars before calculating monthly standard deviation. If this is not done, inflation will introduced a positive trend in USD which will confound the analysis of the trend in monthly standard deviation and therefore the trend in volatility.

ReplyDeleteDiscussion with Erich can be found here if anyone is interested: http://www.energybulletin.net/stories/2012-08-08/new-paradigm-volatile-oil-markets

Delete