I have a joke with a friend of mine that airline pilots are nothing but glorified bus drivers. As cynical as this may be, for the majority of us with regular jobs who fly economy air travel is increasingly becoming like its land-based cousin: cramped, overcrowded and at times downright unpleasant.

Most people living in our modern industrial society take air travel for granted. We think very little about hopping on a plane and travelling around the world for little more than a couple of weeks wages. As jet fuel prices bounce along with the price of crude however many airlines are increasingly struggling to break even. Fuel prices now account for 35 percent of operating costs compared to 15 percent a decade ago. Air travel has always been a fickle business, earning an average net profit of one to two percent, compared with an average of over five percent for U.S. industry as a whole. Research from the 1980s found that some carriers would have zero profitability if they had lost just one out of ten business passengers.

So how does the future look for the airline industry? If recent trends are anything to go by, not good. Not good at all.

Plane Trends

Airlines have increasingly been moving towards smaller aircraft despite the popularity of the “Superjumbo” Airbus A380 since its release in 2007. Airbus has sold 253 A380s while Boeing has orders for 106 747-8s with the large majority of these being used for cargo operations. Richard Aboulafia from Teal Group, an Aerospace and Defense Market Analysis company believes that smaller, sleeker aircraft are the future of international air travel ““The market for large aircraft in general is disappearing fast. Most of the 747-8 planes are cargo. There’s just a limited market.”

Packed Like Sardines

In an effort to increase profits from each flight a number of airline companies are trying to fit more passengers onto each plane. The sale of an extra one or two seats can mean the difference between breaking even and a loss. While standing room only flights appear to be nothing other than a cheap marketing ploy companies have reduced the seat width in order to fit an extra seat in each row.

Air New Zealand recently replaced its older 747s with a significantly narrower 777-300ER. To accommodate the same 3-4-3 seat configuration the new seats are one inch narrower and the aisle has decreased in size as well. Air New Zealand was named the most innovative airline in the world last year Airlinetrends.com and so it is likely that other airline companies will follow suit.

In 2010 an Italian company, Avio Interiors, introduced the world to its “Skyrider” saddle-style seat. Intended for up to four hour long flights the passenger sits at an angle with 23 inches of legroom (compared with 30 inches on a standard configuration) allowing more passengers per flight. Two years later no airlines have yet committed to the Skyrider seating but as fuel prices continue to rise one has to wonder how long it will take before it is seriously considered.

At the other end of the spectrum some airlines have introduced what has colloquially been termed “chub class.” In an effort to accommodate the expanding waistline of Western flyers Airbus is increasing the size of aisle seats to 20 inches wide on its A320 jets while decreasing middle and window seats by one inch. The premium wide seat will be sold at for an extra US$10.

Weight Reduction

Scoot Airlines, based out of Singapore has recently removed television monitors from airplane seats replacing them with Apple iPads. The television monitors and associated electronics are reported to weigh two metric tonnes. According to Bloomberg this has enabled the airline to add 40 percent more seating while decreasing the weight of a fully loaded flight by seven percent.

Extra Charges Everywhere

Traditionally the most successful airlines traded on glamour and providing a service experience. Recent trends however show that airlines are increasingly moving towards a no-frills approach in an effort to cut expenses. To do this airlines are imposing costs on everything possible under the thin veil of “increased consumer choice.” Changes seen over the last few years include the removal of a complimentary item of check-in luggage, the removal of complimentary meals and extra charges for window seats and seats towards the front of the plane. The iPads on Scoot flights mentioned above will cost US$17 to hire for the flight.

Recommendations from a 2005 study suggest that a low-cost strategy should no longer be considered an exception but should rather become the norm for the airline industry. We can see this recommendation playing out today with the stripping of services from flights shifting to an almost purely user pays model.

Case Study: The Air New Zealand Situation

A good example of this new user pays model is Air New Zealand. In 2010 they changed to single class short haul flights with radically rebundled fares. Travellers can now choose from one of four options beginning with a seat, one 7kg carry-on bag, tea, coffee and water and access to some entertainment options but no new release entertainment. At the other end they have the ‘Works Deluxe’ which allows two priority bags, a carry-on bag, meal and drinks, a seat request, a guaranteed empty seat next to the passenger, premium check in, lounge access and better entertainment options.

Being the most innovative airline company does not necessarily make you the most profitable. Air New Zealand announced a 71 percent earning slump in February 2012. As part of its recovery plan the company announced it was cutting 441 jobs. The airline blamed a decrease in passenger numbers as well as as fuel costs NZ$173 million more than forecast. This is despite the airline enjoying “a solid performance from the domestic network including benefits from the Rugby World Cup and improved market share on the Tasman” according to Air New Zealand chairman, John Palmer.

The outgoing chief executive Rob Fyfe says the price of jet fuel has doubled over the last three years and due to the weak global economy it has been difficult to pass on the higher costs to passengers.The inflation adjusted average price of jet fuel was US$3.04 per gallon for the six months to December 31st. Going off jet fuel prices alone it is unlikely the airline will see much of a turn around in profitability for 2012. In the first six months of 2012 the average price barely moved, up US$0.04 to $US3.08.

The full year earnings are not released until the end of August but the few media releases coming out of Air New Zealand the last few months are beginning to sound increasingly desperate. On 19th July 2012 Fyfe and Palmer called for an “urgent review” of New Zealand tourism. Palmer told Parliament's finance and expenditure committee that despite operational improvements (newspeak for job cuts), Air New Zealand's financial performance was not healthy and decreased expenditure was yet to be reflected in its currently "disappointing" share price.

Air New Zealand is looking to focus on its domestic, Australian and Pacific service as these have been the most economically sustainable. According to Fyfe, "An aircraft flying to London and back, a 777-300, it costs $1.25 million to get that aircraft to London and back and over 50% of the cost of fuel, a 737 flying to Auckland - Wellington about 23% of the cost is fuel."

The Global Situation

Globally the situation does not look much better. Some Middle Eastern airlines and Asian carriers are still recording strong growth but they are the exception. The International Air Transport Association (IATA) revised the Middle Eastern profit forecast in March 2012 from USD300 million to USD500 million assuming jet fuel prices stay stable. A spike in oil prices could however could turn the forecast profit into a USD200 million loss for the region’s airlines. According to the IATA average oil prices could reach as high as US$135 per barrel this year in the unlikely event of Iran closing the Strait of Hormuz. Oil prices this high would create a US$5.3billion loss for the global aviation industry.

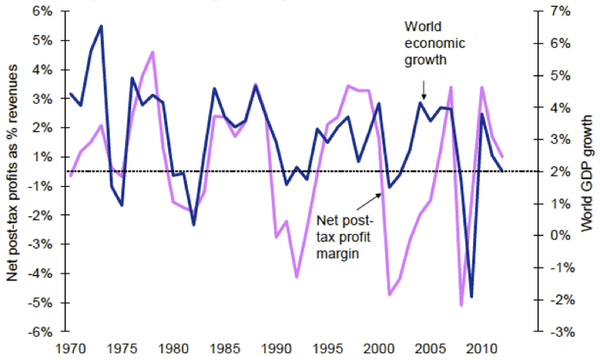

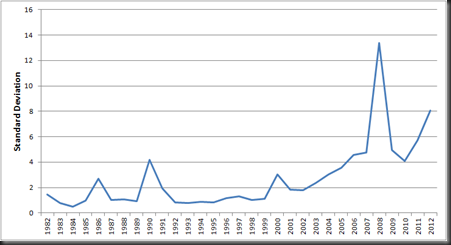

U.S. airline profits have historically followed a cyclical profit-loss pattern of three to five years since U.S. deregulation in 1978. Profit margins have always been thin, sitting at 1.6% during the 1980s and only 1.0% for the period between 1990 and 2000. The early 2000s however saw economic downturn accompanied by huge industry-wide losses of $7 billion in 2001, $7.5 billion in 2002, and $5.3 billion in 2003. The impact of 9/11 and the associated changes to the way airlines run as well as the Dot-com crash cannot be denied either. Between 2000 and 2005 the industry plunged into record operating losses of $40 billion in total.

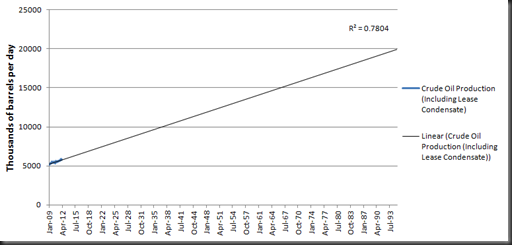

Figure 1: World economic growth and airline profit margins: 1970 to 2011. Source: IATA Financial Monitor for Jan/Feb-2012 released on 01-Mar-2012, sourcing IATA, ICAO & Haver.

Figure 1 clearly illustrates the cyclical nature of the airline industry. Whenever world GDP growth drops below two percent this is reflected by the net post-tax profit margin turning negative.

The director general and CEO of IATA, Tony Tyler, has cautioned that global GDP is not expected to pass two percent in 2012. “The risk of a worsening Eurozone crisis has been replaced by an equally toxic risk – rising oil prices. Already the damage is being felt with a downgrade in industry profits to $3.0 billion… With GDP growth projections now at 2.0%...it will not take much of a shock to push the industry into the red for 2012,” Mr Tyler said.

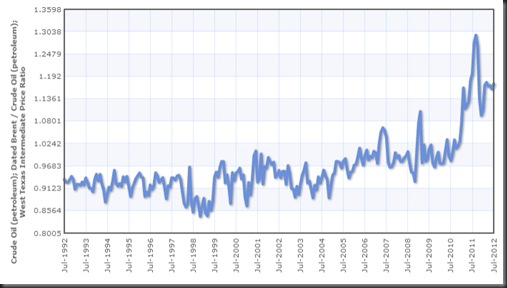

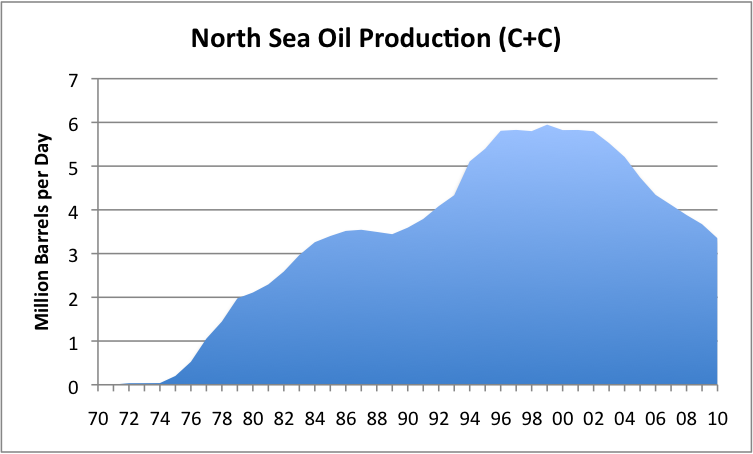

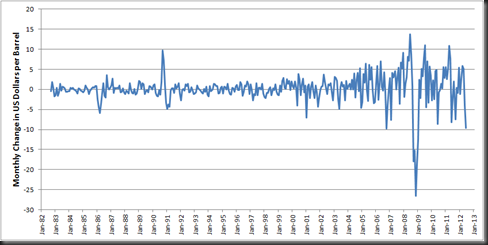

Rising fuel costs have taken a massive chunk out of the airline industries profit margins. The cost of jet fuel closely maps that of crude oil prices. This means that when prices are high at the local pump the airline companies are also hurting.

The IATA has forecast the airline 2012 fuel bill is expected to be $US213 billion, equivalent to 34 percent of total operating costs. The IATA fuel price average for 2012 is currently $US128.6 per barrel which is estimated to add an extra $US31billion onto the forecast 2012 jet fuel bill.

These IATA forecasts illustrate the fragility of the airline industry. Profitability is an elusive prospect for the industry with the IATA commenting that “the best collective margin of the last decade of 2.9% (2007 and 2010) does not cover the cost of capital”. Cargo traffic around the globe declined 1.9 percent in May 2012 compared to May last year. Cargo traffic generated US$66 billion in 2010 but has declined every month since May 2011. “Business and consumer confidence are falling,” Tyler said. “And we are seeing the first signs of that in slowing demand and softer load factors. This does not bode well for industry profitability.”

Dirty Air

If airlines are struggling this much with the current economic conditions it is almost certain that a globally unified approach to carbon taxing would cripple the industry. A report from 2008 found that airlines were emitting 20 percent more carbon dioxide than previously estimated. This could grow to 1.5 billion tons a year by 2025, far more that the worst cast IPCC predictions. As a comparison the entire European Union currently emits 3.1 billion tons of CO2 annually. This emission prediction does assume that oil prices will stay relatively low and that economic growth gets back on track, two assumptions that are looking increasingly unlikely.

Travel While You Can

Environmental concerns aside if you want to travel anywhere in the next five years now is the time to do it. The global economy is extremely fragile at the moment. Petroleum deliveries are at their lowest point since September 2008, with the weakest July demand since 2005 and yet Brent crude prices are still sitting above $US116 per barrel. This is not to mention the impending US “fiscal cliff” where $600bn in tax increases and spending cuts come into effect on January 1, 2013. Unless the US Congress comes to some kind of agreement on raising the debt ceiling again by the end of this year GDP growth could be reduced by four percent, plunging the US into recession. Europe is cannot escape its current quaqmire without huge upheaval and there is now talk that France will be the next to crumble leaving Germany on its own. China’s growth has slowed to a three year low of 7.6 per cent with little sign of recovery in the next few months.

This is all bad news for airlines that are already combatting high fuel prices. I expect to see a number of big name airlines fold or amalgamate in the next two years as financiers can no longer afford to prop up an industry that is hemorrhaging with no relief in sight. This could mean a reduced number of flights, less options of places to travel and skyrocketing ticket prices. While mother nature might thank us for the reduction in emissions the airline industry is running on empty.